WASHINGTON — Mattresses on the floor, next to bunk beds, in meeting rooms and gymnasiums. No access to a bathroom or drinking water. Hourlong lines to buy food at the commissary or to make a phone call.

These are some of the conditions described by lawyers and the people held at immigrant detention facilities around the country over the last few months. The number of detained immigrants surpassed a record 60,000 this month. A Los Angeles Times analysis of public data shows that more than a third of ICE detainees have spent time in an overcapacity dedicated detention center this year.

In the first half of the year, at least 19 out of 49 dedicated detention facilities exceeded their rated bed capacity and many more holding facilities and local jails exceeded their agreed-upon immigrant detainee capacity. During the height of arrest activity in June, facilities that were used to operating with plenty of available beds suddenly found themselves responsible for the meals, medical attention, safety and sleeping space for four times as many detainees as they had the previous year.

“There are so many things we’ve seen before — poor food quality, abuse by guards, not having clean clothes or underwear, not getting hygiene products,” said Silky Shah, executive director of Detention Watch Network, a coalition that aims to abolish immigrant detention. “But the scale at which it’s happening feels greater, because it’s happening everywhere and people are sleeping on floors.”

Shah said there’s no semblance of dignity now. “I’ve been doing this for many years; I don’t think I even had the imagination of it getting this bad,” she added.

Shah said conditions have deteriorated in part because of how quickly this administration scaled up arrests. It took the first Trump administration more than two years to reach its peak of about 55,0000 detainees in 2019.

Assistant Homeland Security Secretary Tricia McLaughlin called the allegations about inhumane detention conditions false and a “hoax.” She said the agency has significantly expanded detention space in places such as Indiana and Nebraska and is working to rapidly remove detainees from those facilities to their countries of origin.

McLaughlin emphasized that the department provides comprehensive medical care, but did not respond to questions about other conditions.

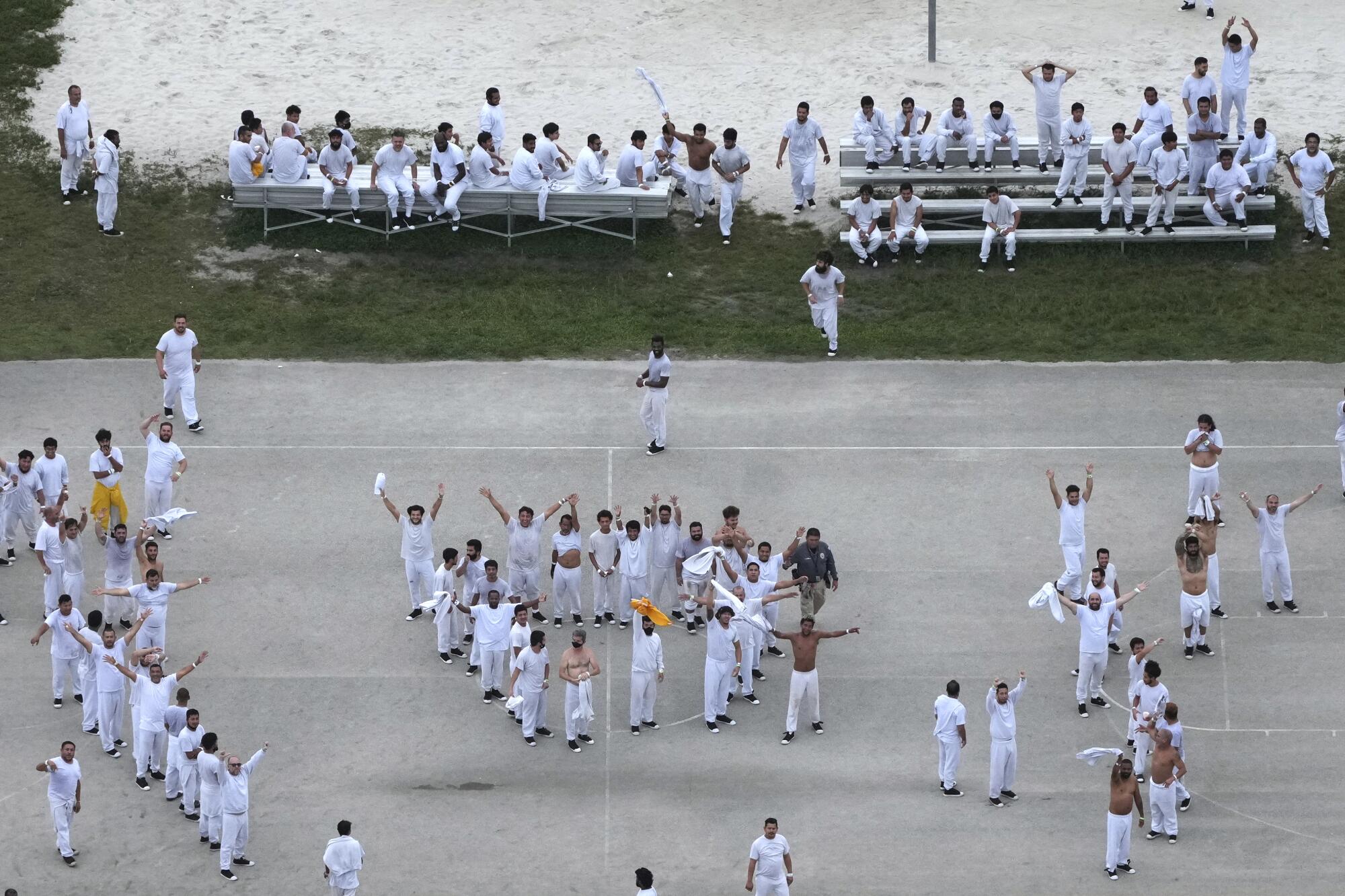

Detainees do stretches outdoors as a helicopter flies overhead at U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Krome detention center in Miami on July 4, 2025.

(Rebecca Blackwell / Associated Press)

At the Krome North Service Processing Center in Miami, the maximum number of detainees in a day in 2024 was 615, four more than the rated bed capacity of 611. In late June of this year, the detainee population reached 1,961, more than three times the capacity. The facility, which is near the Everglades, spent 161 days in the beginning of the year with more people to house than beds.

Miami attorney Katie Blankenship of the legal aid organization Sanctuary of the South represents people detained at Krome. Last month, she saw nine Black men piled into a visitation room, surrounded with glass windows, that holds a small table and four chairs. They had pushed the table against the wall and spread a cardboard box flat across the floor, where they were taking turns sleeping.

The men had no access to a bathroom or drinking water. They stood because there was no room to sit.

Blankenship said three of the men put their documents up to the window so she could better understand their cases. All had overstayed their visas and were detained as part of an immigration enforcement action, not criminal proceedings.

Another time, Blankenship said, she saw an elderly man cramped up in pain, unable to move, on the floor of a bigger room. Other men put chairs together and lifted him so he could rest more comfortably while guards looked on, she said.

Blankenship visits often enough that people held in the visitation and holding rooms recognize her as a lawyer whenever she walks by. They bang on the glass, yell out their identification numbers and plead for help, she said.

“These are images that won’t leave me,” Blankenship said. “It’s dystopian.”

Krome is unique in the dramatic fluctuation of its detainee population. On Feb. 18, the facility saw its biggest single-day increase. A total of 521 individuals were booked in, most transferred from hold rooms across the state, including Orlando and Tampa. Hold rooms are temporary spaces for detainees to await further processing for transfers, medical treatment or other movement into or out of a facility. They are to be used to hold individuals for no more than 12 hours.

On the day after its huge influx, Krome received a waiver exempting the facility from the requirement to log hold room activity. But it never resumed the logs. Homeland Security did not respond to a request for an explanation of the exception.

After reaching their first peak of 1,764 on March 16, the trend reversed.

Rep. Frederica Wilson (D-Fla.) visited Krome on April 24. In the weeks before the visit, hundreds of detainees were transferred out. Most were moved to other facilities in Florida, some to Texas and Louisiana.

“When those lawmakers came around, they got rid of a whole bunch of detainees,” said Blankenship’s client Mopvens Louisdor.

The 30-year-old man from Haiti said conditions started to deteriorate around March as hundreds of extra people were packed into the facility.

Staffers are so overwhelmed that for detainees who can’t leave their cells for meals, he said, “by the time food gets to us, it’s cold.”

Also during this time, from April 29 through May 1, the facility underwent a compliance inspection conducted by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Office of Detention Oversight. Despite the dramatic reduction in the population, the inspection found several issues with crowding and meals. Some rooms exceeded the 25-person capacity for each and some hold times were nearly double the 12-hour limit. Inspectors observed detainees sleeping on the hold room floors without pillows or blankets. Staffers had not recorded offering a meal to the detainees in the hold rooms for more than six hours.

Hold rooms are not designed for long waits

ICE detention standards require just 7 square feet of unencumbered space for each detainee. Seating must provide 18 inches of space per detainee.

LOS ANGELES TIMES

Sanitary and medical attention were also areas of concern noted in the inspection. In most units, there were too many detainees for the number of toilets, showers and sinks. Some medical records showed that staffers failed to complete required mental and medical health screenings for new arrivals, and failed to complete tuberculosis screenings.

Detainees have tested positive for tuberculosis at facilities such as the Anchorage Correctional Complex in Alaska and the Adelanto ICE Processing Center in California. McLaughlin, the Homeland Security assistant secretary, said that detainees are screened for tuberculosis within 12 hours of arrival and that anyone who refuses a test is isolated as a precaution.

“It is a long-standing practice to provide comprehensive medical care from the moment an alien enters ICE custody,” she said. “This includes medical, dental, and mental health intake screening within 12 hours of arriving at each detention facility, a full health assessment within 14 days of entering ICE custody or arrival at a facility, and access to medical appointments and 24-hour emergency care.”

Facility administrators built a tented area outside the main building to process arriving detainees, but it wasn’t enough to alleviate the overcrowding, Louisdor said. Earlier this month, areas with space for around 65 detainees were holding more than 100, with cots spread across the floor between bunk beds.

Over-capacity facilities can feel extremely cramped

Bed capacity ratings are based on facility design. Guidelines require 50 square feet of space for each individual. When buildings designed to those specifications go over their rated capacity, there is not enough room to house additional detainees safely and comfortably.

American Correctional Association and Immigration and Customs Enforcement

LOS ANGELES TIMES

Louisdor said a young man who uses a wheelchair had resorted to relieving himself in a water bottle because staffers weren’t available to escort him to the restroom.

During the daily hour that detainees are allowed outside for recreation, 300 people stood shoulder to shoulder, he said, making it difficult to get enough exercise. When fights occasionally broke out, guards could do little to stop them, he said.

The line to buy food or hygiene products at the commissary was so long that sometimes detainees left empty-handed.

Louisdor said he has bipolar disorder, for which he takes medication. The day he had a court hearing, the staff mistakenly gave him double the dosage, leaving him unable to stand.

Since then, Louisdor said, conditions have slightly improved, though dormitories are still substantially overcrowded.

In California, detainees and lawyers similarly reported that medical care has deteriorated.

Tracy Crowley, a staff attorney at Immigrant Defenders Law Center, said clients with serious conditions such as hypertension, diabetes and cancer don’t receive their medication some days.

Cells that house up to eight people are packed with 11. With air conditioning blasting all night, detainees have told her the floor is cold and they have gotten sick. Another common complaint, she said, is that clothes and bedding are so dirty that some clients are getting rashes all over their bodies, making it difficult to sleep.

Luis at Chicano Park in San Diego on Aug. 23, 2025.

(Ariana Drehsler / For The Times)

One such client is Luis, a 40-year-old from Colombia who was arrested in May at the immigration court in San Diego after a hearing over his pending asylum petition. Luis asked to be identified by his middle name out of concern over his legal case.

When he first arrived at Otay Mesa Detention Center, Luis said, the facility was already filled to the maximum capacity. By the time he left June 30, it was overcrowded. Rooms that slept six suddenly had 10 people. Mattresses were placed in a mixed-use room and in the gym.

Luis developed a rash, but at the medical clinic he was given allergy medication and sleeping pills. The infection continued until finally he showed it over a video call to his mother, who had worked in public health, and she told him to request an anti-fungal cream.

Luis was held at Otay Mesa Detention Center after his May arrest. It was at capacity when he arrived but by the time he left in June, it was overcrowded, he said.

(Ariana Drehsler / For The Times)

Other detainees often complained to Luis that their medication doses were incomplete or missing, including two men in his dorm who took anti-psychotic medication.

“They would get stressed out, start to fight — everything irritated them,” he said. “That affected all of us.”

Crowley said the facility doesn’t have the infrastructure or staff to hold as many people as are there now. The legal system also can’t process them in a timely manner, she said, forcing people to wait months for a hearing.

The administration’s push to detain more people is only compounding existing issues, Crowley said.

“They’re self-imposing the limit, and most of the people involved in that decision-making are financially incentivized to house more and more people,” she said. “Where is the limit with this administration?”

Members of the California National Guard load a truck outside the ICE Processing Center in Adelanto, Calif., on July 11, 2025.

(Patrick T. Fallon / AFP/Getty Images)

Other facilities in California faced similar challenges. At the Adelanto ICE Processing Center, the number of detainees soared to 1,000 from 300 over a week in June, prompting an outcry over deteriorated conditions.

As of July 29, Adelanto held 1,640 detainees. The Desert View Annex, an adjacent facility also operated by the GEO Group, held 451.

Disability Rights California toured the facility and interviewed staffers and 18 people held there. The advocacy organization released a report last month detailing its findings, including substantial delays in meal distribution, a shortage of drinking water, and laundry washing delays, leading many detainees to remain in soiled clothing for long periods.

In a letter released last month, 85 Adelanto detainees wrote, “They always serve the food cold … sometimes we don’t have water for 2 to 7 hours and they said to us to drink from the sink.”

At the Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Ga., Rodney Taylor, a double amputee, was rendered nearly immobile.

Taylor, who was born in Liberia, uses electronic prosthetic legs that must be charged and can’t get wet. The outlets in his dormitory were inoperable, and because of the overcrowding and short-staffing, guards couldn’t take him to another area to plug them in, said his fiancee, Mildred Pierre.

“When they’re not charged they’re super heavy, like dead weight,” she said. It becomes difficult to balance without falling.

Pierre said the air conditioning in his unit didn’t work for two months, causing water to puddle on the floor. Taylor feared he would slip while walking and fall — which happened once in May — and damage the expensive prosthetics.

Last month, Taylor refused to participate in the daily detainee count, telling guards he wouldn’t leave his cell unless they agreed to leave the cell doors open to let the air circulate.

“They didn’t take him to charge his legs and now they wanted him to walk through water and go in a hot room,” Pierre recalled. “He said no — he stood his ground.”

Several guards surrounded him, yelling, Pierre said. They placed him in solitary confinement for three days as punishment, she said.